Image copyright iStock

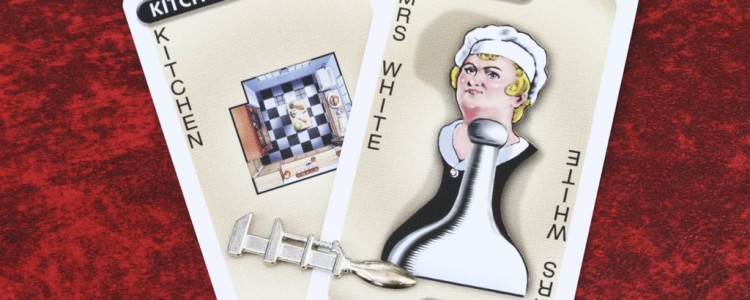

Image copyright iStock One of the six original characters of the board game Cluedo, Mrs White, has been killed off by game makers Hasbro.

The long-time housekeeper is being replaced by Dr Orchid, who has a PhD in plant toxicology and was home-schooled by Mrs White herself.

The game sees players work out which of the characters has committed a murder at Tudor Mansion, in which room and with what weapon.

It is the first time Hasbro has killed off a Cluedo character since 1949.

The Dr Orchid character is said to have been privately educated in Switzerland “until her expulsion following a near-fatal daffodil poisoning incident”.

Image copyright PA

Image copyright PA She is also the adoptive daughter of Samuel Black, who owns the mansion where the murderous events take place.

Craig Wilkins, marketing director for Hasbro in the UK and Ireland, said: “It was a difficult decision to say goodbye to Mrs White, but after 70 years of suspicious activity we decided that one of the characters had to go.

“Dr Orchid is a brilliant new character with a rich back story and links to the Black fortune.”

The game’s six characters are Miss Scarlett, Professor Plum, Mrs Peacock, the Reverend Green, Colonel Mustard and the new Dr Orchid.

All the existing characters have been recently revamped, apart from Colonel Mustard.

Read more: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-36714720