Image copyright Alamy

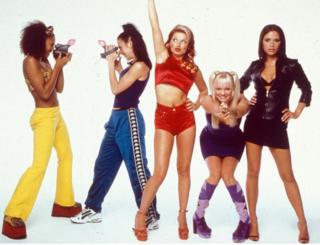

Image copyright Alamy On 7 July 1996, a single from five unknown girls – Victoria Adams, Mel Brown, Emma Bunton, Melanie Chisholm and Geri Halliwell – was released and made them household names around the world.

The Spice Girls’ Wannabe was the UK number one single for seven weeks and in February 1997, topped the US Billboard Hot 100 for four weeks. Two decades on, the group’s influence continues to be identifiable in popular culture – and in some unexpected ways. From how TV and newspapers cover music, to the way stars brand themselves, the Spice Girls influenced many of the rules for 21st Century pop stars.

Before 1996, manufactured groups were expected to obey management and music label orders. Even though the five were put together by Bob and Chris Herbert, the group soon decided to replace the father-and-son management team with Simon Fuller. And against record company advice, they also chose their first single.

“If they decided they wanted to do something, then that’s what was going to happen,” says Wannabe’s co-writer Richard “Biff” Stannard.

Visual artist Liz West, a Guinness Book of Records entrant for the world’s largest collection of Spice memorabilia (nearly 5,000 items), agrees.

“When it was suggested to people what their first single should be, they had already chosen it,” she says.

Wannabe’s release came the year after the battle for chart dominance between the all-male Britpop groups Blur and Oasis. Timing was ripe for an opinionated girl group, says Paul Gorman, the first writer to interview them for Music Week.

Image copyright PA

Image copyright PA “Britpop was a bunch of blokes going through their dads’ record collections,” he says.

Wannabe’s nursery-rhyme-style hypnotic chant secured a broad coalition of fans including those hard-to-get pre-teens who the music industry had previously considered as a small market.

And in the following years, in the run-up to the millennium, the influence of the Spice Girls on this audience, led to the emergence of other acts aimed at a younger market. As a result, acts such as S Club 7, B*Witched, Aqua, Hanson, Steps and Billie Piper started to top the charts.

Kim Glover, the manager of girlband B*Witched, who had four number one singles in the slipstream of Spice success says: “They were very different from what had gone before them. Wannabe jumped out the radio – from the very first bar, you were hooked.”

Image copyright Reuters

Image copyright Reuters The single was a springboard for 80m global album sales, and the now ingrained slogan “Girl Power”.

Yet not everyone was convinced. Girl Power, according to Gorman, was “in many respects an empty phrase”.

“But it did mark a change in the way strong young British women saw themselves in the ’90s and reflected the rise of ladette culture.”

“Half of it was a marketing man’s slogan,” says Liz West. “But as an 11-year-old girl, it instilled confidence in me.”

Glover is more positive. “I personally loved it. As a woman in the music business, it resonated with me.”

Many current female stars such as Adele, Emma Stone, Jennifer Lawrence and Emma Watson have revealed they were and still are fans.

Radio 1 DJ Jo Whiley told last month’s Radio Times that Adele had Spice Girls photos on her fridge. She sang Spice Up Your Life at her June Amsterdam gig.

“Adele and other female stars would have been brought up in a world where you couldn’t avoid them. Mums, grandparents, the whole family went to the concerts,” says West.

The diverse identities of Posh, Scary, Baby, Sporty and Ginger (as nicknamed by Top of the Pops magazine) were also a selling point, and a departure from previous bands.

Image copyright Alamy

Image copyright Alamy “They had five personalities and you could connect to one or more of them,” says West. “They didn’t dress the same like previous girl bands like The Supremes in their sequinned gowns. Even The Beatles dressed the same when they started.”

Mainstream media were receptive to these personalities.

“UK tabloids were at their zenith,” remembers Alan Edwards, their publicist at the peak of their success. “The Sun was registering a 4.5m daily sale. All five girls grew up with pop gossip and instinctively understood it.”

This media interest would balloon when Adams started dating Manchester United footballer David Beckham. Following Charles and Diana’s divorce, tabloid interest in a Celebrity Power Couple had Edwards working, as he now admits, “around the clock”.

“The mix of pop music and football – the two modern religions – was a potent one. You have to go back to England captain Billy Wright dating Joy from The Beverley Sisters in the late ’50s for anything like it.

“The thrones they sat on at their wedding may have been done tongue in cheek, but Buckingham Palace even received letters from all over the world addressed to David and Victoria.”

Such fascination continues with Kim Kardashian and Kanye West, Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, Jay-Z and Beyonce and many other high-wattage couples. This dismays some, including Gorman.

Image copyright PA

Image copyright PA “They inaugurated the era of cheesy celebrity obsession which pertains today,” he says. “There is lineage from them to the Kardashianisation not only of the music industry, but the wider culture.”

Their girl-next-door appeal predated TV stations’ realisation that they could create instant pop stars with Pop Idol, American Idol, The X Factor and The Voice. Girls Aloud, Fifth Harmony, Little Mix and One Direction were all formed through talent shows.

Stars had used brand endorsements but the Spice brand was the first to propel the success of the band.

Martin Brooks, now a marketing expert at Havas London, explains: “Before, artists like Michael Jackson would see a Pepsi deal as eroding his or her credibility for money. Whereas The Spice Girls’ musical credibility was never an issue. The question was, ‘How can we make as much money as quickly as possible and how can we use brands to drive that fame?'”

There was Spice branding on more than 100 products including cameras, scooters, crisps and a Pepsi promotion where 20 ring pulls collected from cans would earn fans the CD of an unreleased Spice track.

“Such was their power that people would happily spend 8-10 on fizzy drinks to get a free CD,” says Brooks who worked on it. “It was by far the most successful promotion Pepsi had done.”

According to Edwards: “The band was a brand and comfortable with it too.”

West adds that “you could buy their cards at Clintons, their soft drinks at Asda, their magazine at the newsagents, their book at Waterstone’s, their record at HMV and their T-shirt at Our Price.”

This level of product endorsement has since been exploited by other stars such as Beyonce, Justin Bieber and sports stars like Andy Murray and Beckham (both managed by Fuller).

Endorsement is a key way for pop stars facing a decline in record sales to make money. Glover points out that “the Spice branding was a real step forward and is a mega-important marketing stream which I open to my artists constantly”.

For all that modern stars from Katy Perry to Lionel Messi exploit brand endorsements and attract tabloid coverage, the scale of the Spice Girls’ breakthrough in 1996 is unlikely to be repeated – at least not by a music act.

“If someone says the words ‘I Tell You What I Want’ to me they go into the whole song,” says Richard Stannard. “I don’t know if One Direction will have that in 20 years’ time. There will never be something that big again. It was like Harry Potter.”

Follow us on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, on Instagram at bbcnewsents, or email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk.

Read more: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-36714177