All the authors said was that among the many hospitalized patients who were given a dose of opioid for their acute injury, very few developed addiction. That is all it said. It said nothing about what happens to patients who take these medicines indefinitely.

Yet those few sentences got transformed by relentless marketing into “opiates are not addictive.” Which was as crazy as saying “tobacco is not addictive,” if someone smoked four cigarettes and did not become a chain-smoker. It was blatantly irresponsible medicine. But it worked. Prescriptions soared.

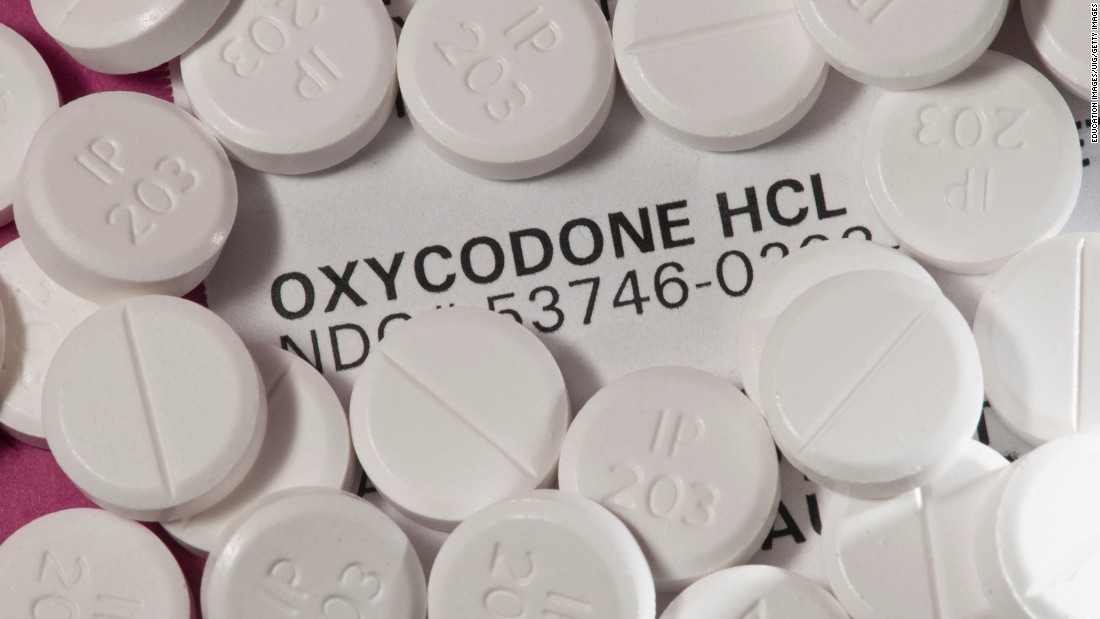

By now, you know that the U.S.

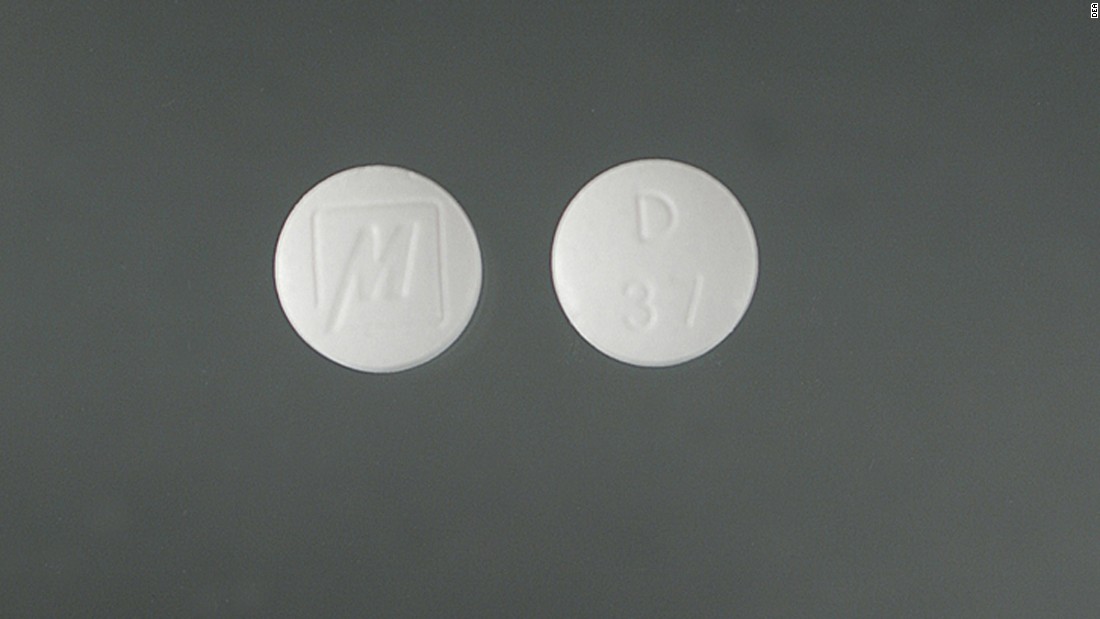

consumes 80% of the world’s opioid painkillers while comprising just 5% of the world’s population. And as the sales have increased, so, too, have the overdose deaths and the rates of admission to addiction treatment centers. In 1999, 4,030 Americans lost their lives to accidental opiate overdose. In 2014, that number had i

ncreased to 18,893. That is more than six World Trade Centers.

Some of you no doubt are asking: Where have the good doctors been in all this? Aren’t they supposed to be watching out for our safety? The answer to that question is very discouraging, but I can reach no other conclusion after studying and fighting this problem for the last 10 years. The answer is we are right where we have always been — minding the register.

The values currently prioritized by medicine were made explicit to me several years ago. During my annual performance review, my medical director told me: “You know, we are so proud of you for all the work you are doing fighting the opiate prescription problem. But it is such a fine line between increasing the risk of addiction and HCAHPS scores.”

Wow. Every health care professional reading this knows exactly what I am talking about.

HCAHPS stands for Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. These are “patient satisfaction” surveys and they talk about pain management specifically. Hospitals are required to participate in these surveys and reimbursement is tied to how well they do. Hence, every hospital administrator and department chair is acutely aware of their “score.”

If this sounds too fuzzy and “Kumbaya” for you, I would point out that this exact sentiment is expressed in the

Hippocratic oath. The 1964 version (which I recited in medical school) admonishes us to remember “that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy and understanding may outweigh the surgeon’s knife or the chemist’s drug.”

In America, we are far too heavy on the knives and drugs, and far too light on the warmth and sympathy.

I realize that making these fundamental changes to our health care delivery system will be very difficult. There are a lot of powerful interests with very little to gain by changing the current system. But change must happen. Because the yearly body count due to the opiate epidemic is simply not acceptable.

I believe we can do better. For the memory of Prince and the thousands of others whom we have lost too soon.